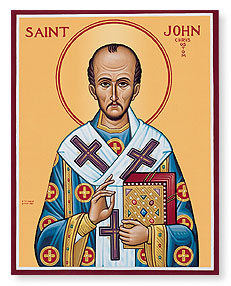

St. John the Eloquent

John Chrysostom also known as St. John the Eloquent 349 – 407, Archbishop of Constantinople, was an important Early Church Father. St. John the Eloquent is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and political leaders, the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, and his ascetic sensibilities. The epithet Χρυσόστομος (Chrysostomos, anglicized as Chrysostom) means “golden-mouthed” in Greek and denotes his celebrated eloquence.

St. John the Eloquent is honored as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches, as well as in some others. The Eastern Orthodox, together with the Byzantine Catholics, hold him in special regard as one of the Three Holy Hierarchy (alongside Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus). In the Roman Catholic Church he is recognized as a Doctor of the Church and commemorated on 13 September. Other churches of the Western tradition, including some Anglican provinces and some Lutheran churches, also commemorate him on 13 September. However, certain Lutheran churches and Anglican provinces commemorate him on the traditional Eastern feast day of 27 January. The Coptic Church also recognizes him as a saint (with feast days on 16 Thout and 17 Hathor).

St. John the Eloquent was born in Antioch in 349 to Greco-Syrian parents. Different scholars describe his mother Anthusa as a pagan or as a Christian, and his father was a high-ranking military officer. John’s father died soon after his birth and he was raised by his mother. He was baptised in 368 or 373 and tonsured as a reader (one of the minor orders of the Church).

As a result of his mother’s influential connections in the city, John began his education under the pagan teacher Libanius. From Libanius, John acquired the skills for a career in rhetoric, as well as a love of the Greek language and literature.

As he grew older, however, John became more deeply committed to Christianity and went on to study theology under Diodore of Tarsus, founder of the re-constituted School of Antioch. According to the Christian historian Sozomen, Libanius was supposed to have said on his deathbed that John would have been his successor “if the Christians had not taken him from us”.

St. John the Eloquent lived in extreme asceticism and became a hermit in about 375; he spent the next two years continually standing, scarcely sleeping, and committing the Bible to memory. As a consequence of these practices, his stomach and kidneys were permanently damaged and poor health forced him to return to Antioch.

In Antioch, over the course of twelve years (386–397), St. John the Eloquent gained popularity because of the eloquence of his public speaking at the Golden Church, Antioch’s cathedral, especially his insightful expositions of Bible passages and moral teaching. The most valuable of his works from this period are his Homilies on various books of the Bible. He emphasised charitable giving and was concerned with the spiritual and temporal needs of the poor. He spoke against abuse of wealth and personal property:

Do you wish to honour the body of Christ? Do not ignore him when he is naked. Do not pay him homage in the temple clad in silk, only then to neglect him outside where he is cold and ill-clad. He who said: “This is my body” is the same who said: “You saw me hungry and you gave me no food”, and “Whatever you did to the least of my brothers you did also to me”… What good is it if the Eucharistic table is overloaded with golden chalices when your brother is dying of hunger? Start by satisfying his hunger and then with what is left you may adorn the altar as well.

His straightforward understanding of the Scriptures – in contrast to the Alexandrian tendency towards allegorical interpretation – meant that the themes of his talks were practical, explaining the Bible’s application to everyday life. Such straightforward preaching helped Chrysostom to garner popular support. He founded a series of hospitals in Constantinople to care for the poor.[19]

One incident that happened during his service in Antioch illustrates the influence of his homilies. When Chrysostom arrived in Antioch, Flavian, the bishop of the city had to intervene with Emperor Theodosius I on behalf of citizens who had gone on a rampage mutilating statues of the Emperor and his family. During the weeks of Lent in 387, John preached more than twenty homilies in which he entreated the people to see the error of their ways. These made a lasting impression on the general population of the city: many pagans converted to Christianity as a result of the homilies. As a result, Theodosius’ vengeance was not as severe as it might have been.

In the autumn of 397, St. John the Eloquent was appointed Archbishop of Constantinople, after having been nominated without his knowledge by the eunuch Eutropius. He had to leave Antioch in secret due to fears that the departure of such a popular figure would cause civil unrest.

During his time as Archbishop St. John the Eloquent adamantly refused to host lavish social gatherings, which made him popular with the common people, but unpopular with wealthy citizens and the clergy. His reforms of the clergy were also unpopular. He told visiting regional preachers to return to the churches they were meant to be serving—without any payout.

His time in Constantinople was more tumultuous than his time in Antioch. Theophilus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, wanted to bring Constantinople under his sway and opposed John’s appointment to Constantinople. Theophilus had disciplined four Egyptian monks (known as “the Tall Brothers“) over their support of Origen‘s teachings. They fled to John and were welcomed by him. Theophilus therefore accused John of being too partial to the teaching of Origen. He made another enemy in Aelia Eudoxia, wife of Emperor Arcadius, who assumed that John’s denunciations of extravagance in feminine dress were aimed at herself. Eudoxia, Theophilus and other of his enemies held a synod in 403 (the Synod of the Oak) to charge John, in which his connection to Origen was used against him. It resulted in his deposition and banishment. He was called back by Arcadius almost immediately, as the people became “tumultuous” over his departure, even threatening to burn the royal palace. There was an earthquake the night of his arrest, which Eudoxia took for a sign of God‘s anger, prompting her to ask Arcadius for John’s reinstatement.

Peace was short-lived. A silver statue of Eudoxia was erected in the Augustaion, near his cathedral. John denounced the pagan dedication ceremonies. He spoke against her in harsh terms: “Again Herodias raves; again she is troubled; she dances again; and again desires to receive John’s head in a charger”,[24] an allusion to the events surrounding the death of John the Baptist. Once again he was banished, this time to the Caucasus in Abkhazia.

Around 405, Chrysostom began to lend moral and financial support to Christian monks who were enforcing the emperors’ anti-Pagan laws, by destroying temples and shrines in Phoenicia and nearby regions.

Faced with exile, John Chrysostom wrote an appeal for help to three churchmen: Pope Innocent I, the Bishop of Milan, Venerius, and the third to the Bishop of Aquileia, Chromatius. In 1872, church historian William Stephens wrote, “The Patriarch of the Eastern Rome appeals to the great bishops of the West, as the champions of an ecclesiastical discipline which he confesses himself unable to enforce, or to see any prospect of establishing. No jealousy is entertained of the Patriarch of the Old Rome by the Patriarch of the New Rome. The interference of Innocent is courted, a certain primacy is accorded him, but at the same time he is not addressed as a supreme arbitrator; assistance and sympathy are solicited from him as from an elder brother, and two other prelates of Italy are joint recipients with him of the appeal.”

John wrote letters which still held great influence in Constantinople. As a result of this, he was further exiled from the Caucasus (where he stayed from 404 to 407) to Pitiunt (Pityus) (in modern Abkhazia) where his tomb is a shrine for pilgrims. He never reached this destination,, as he died at Comana Pontica on 14 September 407 during the journey. His last words are said to have been “δόξα τῷ θεῷ πάντων ἕνεκεν” (Glory be to God for all things).

These homilies helped to mobilize public opinion, and the patriarch received permission from the emperor to return Chrysostom’s relics to Constantinople, where they were enshrined in the Church of the Holy Apostles on 28 January 438. The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates him as a “Great Ecumenical Teacher”, with Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian. These three saints, in addition to having their own individual commemorations throughout the year, are commemorated together on 30 January, a feast known as the Synaxis of the Three Hierarchs.

John Chrysostom died in the city of Comana in the year 407 on his way to his place of exile. There his relics remained until 438 when, thirty years after his death, they were transferred to Constantinople during the reign of the Empress Eudoxia‘s son, the Emperor Theodosius II (408–450), under the guidance of John’s disciple, St. Proclus, who by that time had become Archbishop of Constantinople (434–447).

Most of John’s relics were looted from Constantinople by Crusaders in 1204 and taken to Rome, but some of his bones were returned to the Orthodox Church on 27 November 2004 by Pope John Paul II. They are now enshrined in the Church of St. George, Istanbul.

The skull, however, having been kept at the monastery at Vatopedi on Mount Athos in northern Greece, was not among the relics that were taken by the crusaders in the 13th century. In 1655, at the request of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, the skull was taken to Russia, for which the monastery was compensated in the sum of 2000 rubles. In 1693, having received a request from the Vatopedi Monastery for the return of St John’s skull, Tsar Peter the Great ordered that the skull remain in Russia but that the monastery was to be paid 500 rubles every four years. The Russian state archives document these payments up until 1735. The skull was kept at the Moscow Kremlin, in the Cathedral of the Dormition of the Mother of God, until 1920, when it was confiscated by the Soviets and placed in the Museum of Silver Antiquities. In 1988, in connection with the 1000th Anniversary of the Baptism of Russia, the head, along with other important relics, was returned to the Russian Orthodox Church and kept at the Epiphany Cathedral, until being moved to the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour after its restoration.

Today, the monastery at Vatopedi posits a rival claim to possessing the skull of John Chrysostom, and there a skull is venerated by pilgrims to the monastery as that of St John. Two sites in Italy also claim to have the saint’s skull: the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence and the Dal Pozzo chapel in Pisa. The right hand of St. John is preserved on Mount Athos, and numerous smaller relics are scattered throughout the world.